Link to Part 1

Here, I'm going to describe how I created a repertoire database and how I maintain it. It's based on the following premises:

1. The database should be relevant to your own games, not necessarily grandmaster praxis. If your opponents are more likely to play the Steinitz or Cozio variations of the Spanish rather than the main-line Closed Spanish, then your repertoire database should reflect this.

2. Studying the opening should be largely driven by the analysis of your own games.

3. A main reason for maintaining a repertoire is to record what you have chosen to play in a given circumstance, and to record what you've encountered in the past.

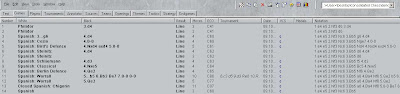

The method I'm advocating is to start a "lean" database similar to that described in my previous post, and then to add to this skeletal database as you play games. I've constructed a "lean" database of some key Spanish opening variations, plus a couple Philidor positions (for reasons I'll explain later). Again, click on any graphic to see the larger version.

These are positions I would encounter as White. I've also decided to include a couple main lines: the Worrall for White and the Closed Spanish, Chigorin Defense as Black. If you've read my series on preparing an opening, you'll see that I advocate determining a "main line" that you would play against your opponent's "best" moves, and then build from there. As you determine these main lines, you can record them in your repertore.

The naming system is similar to that in Lopez's articles. The general opening description is in the "White player" field, and the moves are entered into the "Black player" field. If you run out of room there, you can continue into the "Tournament" field. The more descriptive the entry in the White Player field, the more you can truncate. For example, if I'm familiar with the main-line of the Worrall I could perhaps just have "Spanish: Worrall mainline to 10.Re1" and save the Black and Tournament fields for more detailed continuations. Also, if some responses are forced or very common I could consider skipping over them (e.g. for Bird's defense I could just put 5.0-0 in the Black field). What's important is that you can look at the game header and know exactly what position it deals with.

If you are familiar with the Medals feature of ChessBase, you can use them to deliver additional information at a glance. I have the following reminder saved as a text entry in my personal repertoire:

For this database, I am going to interpret the medals as follows:

In White repertoire: Defense (light grey)

In Black repertoire: Tactical Blunder (black)

Novelty: Novelty (blue)

Surprise weapon (rare or tricky line): Tactics (deep red)

Require Research: User (cyan) (easy to mark in a game list with + key)

Gambit: Sacrifice (bright red)

So, for example, in a mish-mash of French Defense lines I can tag which ones I may encounter as White by tagging the key opening move with the "Defense" medal. If I've decided I need to think about a certain line, I can just highlight the game in the database window and hit "+" on the numerical keypad, and it automatically assigns the "User" medal to the entire game. I can use these medals to also mark which lines are my own "home cooking" as opposed to standard book lines.

(Aside: deciding on the main lines you want to play can involve some reflection and study. I have recently taken to creating a database that I call "Laboratory" and save ponder-worthy lines to it, and then later determine what my main line will be. When I've worked it out, I transfer the result to my repertoire database).

In these lines, the critical opening positions so far are marked at a position I would reach, with my opponent to play. This means that if I do a repertoire search, I will get games returned that show where I've stayed "in book". You can also mark positions that your opponent would reach and where you are to play. A repertoire search then could return games where your opponent was "in book" and where you may have deviated. When considering whether to have a line for a certain critical position in the database, ask yourself if you would be interested in a search result for that position. This may not be clear until you've actually done a few practice searches, so don't sweat it for now.

So, what's wrong with the repertoire database lineup shown above? Well, let's do a test search using an issue of The Week in Chess. The results:

1. Philidor (3.d4): 12 games

2. Spanish: Steinitz (4.d4): 2 games

3. Spanish: 92 games

As I mentioned in my previous post, the order that the games appear in the database is of critical importance. Here, the only subvariation of the Spanish that appeared above the "catch-all" Spanish position (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5) was the Steinitz. All non-Steinitz games got caught in that filter.

I sort my repertoire database manually, approximately by the ECO code, but tweak the sort orders to avoid search problems. For example, I manually moved the games around to the following order, and fixed them in this position by selecting "Tools-->Fix Sort Order". It re-saves the database with the new game order. It now looks like:

Which now returns a more useful search result:

12

Philidors

2

Steinitz

1 Berlin

3

Worralls

1

Chigorin

77 Spanish

The last entry shows all the Spanish variations that didn't match one of our specific variations. Further additions to the repertoire database will

tweeze them apart.

However, you still have to be careful about transpositions, and there isn't much you can do about that. For example, after 1.e4 e5 2.

Nf3 d6 3.d4

Nc6, I play by transposing to the Spanish

Steinitz with 3.

Bb5. Yet any games that I played in this line would be filed under the

Philidor if I used the repertoire database shown here. In some cases you can bump the less-likely move order further down the list, but that can get messy, especially when dealing with big ECO differences such as here. Alternatively, you can make a new

Philidor entry for the moves up to 3...

Nc6, and annotate it so as to point out the transposition there. This is one area where programs like

Bookup and Chess Position Trainer have an advantage...they catch all transpositions for you.

I do not recommend that you attempt to enter your entire repertoire into the database...it's not worth your time. Put in a few of the lines you commonly see, and try a few "generate repertoire" scans on your databases to make sure you're doing it right. Then, as you play games and analyze them, you can add the results. Here's a couple of examples on how you may go about adding to the

repertoire database shown above. This will also highlight how I think one should approach studying the opening.

On a game-by-game basis, you can load your game into

ChessBase for analysis. As part of your analysis, you can find out where the game left the main lines, and where it left all previous knowledge, by right-clicking on the board and selecting "Editorial Annotation(RR)":

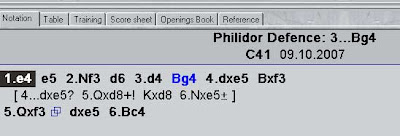

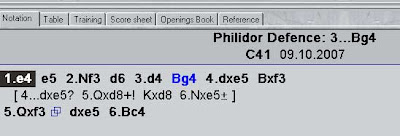

In this case, I had a

Philidor with 3...

Bg4, which currently is not in my repertoire database. In the course of my analysis, I tried to determine a main line and where I could have played better.

I'm using a custom opening book that I made from grandmaster games as

ChessBase's default opening book, plus the

ChessBase megabase as the reference database. The Editorial Annotations tend to show where you deviated from the best book lines, and from the entire

megabase (marking the first new move with an "N" for novelty). This is no substitute for an independent assessment...you should determine for yourself what you'd like to play. But it's a quick and dirty way of seeing where you went off the beaten path.

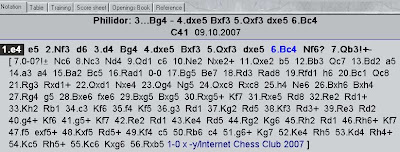

Here, my moves seemed reasonable. My 7

th move was passable, and one GM played 7.c3 here. However, the reference database shows 7.

Qb3! to be the most common move here, and Fritz shows that it's winning.

How you choose to save these results to your database is up to you, but here is how I would approach it:

1. The move 3...

Bg4 deserves its own entry. With some experience in these lines, I can tell you it's a common move at my level so it's good to be able to play consistently here. 4.

dxe5 will usually prompt Black to play 4...

Bxf3, because of the threat of 4...

dxe5 5.

Qxd8+

Kxd8 6.

Nxe5. After 4...

Bxf3 5.

Qxf3

dxe5, Black has given up the bishop pair. So I would enter this game into the repertoire database:

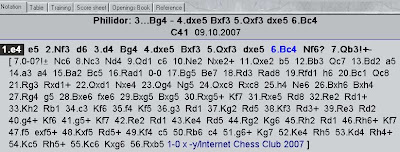

I've included my moves up to 6.

Bc4, because it constitutes my chosen "main line" response. For this minor variation I don't feel compelled to analyze out to the end of the opening...this position is already comfortable for White. However, I missed a critical response to my opponent's subsequent play. Depending on its importance, I could choose not to record it (tactical oversight), incorporate it as a game footnote, or give it its own entry. I think that since it was missed by a Grandmaster, and because Black's erroneous move feels natural, it deserves its own entry.

One option is to go back to the actual game, and right-click on the board and select "Add to Repertoire". If you select "Merge with

Philidor Defense: 3...

Bg4" it will appear as a variation in that entry. I think it's more important than that, so I create a new entry for the line up to 6.

Bc4. I then go back to the actual game, and select "add to repertoire" to add my own inferior game to the repertoire. The result:

I like to include the games where I didn't play the best move in my repertoire databases, for a few reasons. One is that it helps to cement the variation in your mind. Another is that you may find that you repeatedly make the same mistake, indicating you need to think about the line a bit more. Finally, if you perform a "find position in

" function, it will determine if you've had the position before even if it's not part of the repertoire main lines.

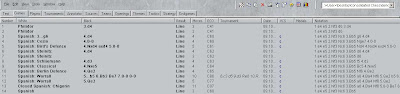

If you're tardy (like I've been) or just starting out, you can also generate a repertoire of a batch of your games, and look to see where the filter is getting badly clogged. This either indicates a gap in your repertoire database that can be filled using your own games, or indicates a possible problem with the sort order that needs to be tweaked. I go through, analyze the games, and add new entries to my repertoire as needed. When working on a batch, I flag each completed game with the User medal to indicate that I've already taken care of it.

This is taken from an actual repertoire search of my backlog of ICC games:

I see that I played 3 Pozianis. I can click on each game individually, or load all three. The latter produces a window like this:

I preview the games here, then open individual game windows for them if they need to be annotated/added to repertoire/saved separately. Don't try to annotate in this 3-game view... the save/replace buttons are greyed out and you'll lose all your work.

I preview the games here, then open individual game windows for them if they need to be annotated/added to repertoire/saved separately. Don't try to annotate in this 3-game view... the save/replace buttons are greyed out and you'll lose all your work.

When I'm done reviewing, analyzing, and saving the results wherever they belong (personal game collection, repertoire database, tactics, blunders, endgames, whatever) I click on the game in the game list and hit "+" on the number keypad to flag the game with the cyan user medal, so I know that I've taken care of it. If I resume reviewing my games at a later date I can tell at a glance if I've taken care of a game or not.

Currently GrandpatzerBase is at 390 entries and growing. Many of these openings have multiple variations, indicating I've experienced them more than once or found them ponder-worthy. One advantage of such a database is that it indicates if you keep making the same mistake. Each time you enter your faulty play into the database, and you see your previous foibles, it reinforces that you need to understand the position better.

If you've never saved and analyzed your games before (even blitz), you have no idea how much knowledge gained from experience you're letting slip through your fingers...and not just opening theory, but tactics, strategy and endgames too. I haven't been as zealous with the last three (my tactics, blunders and endgame databases are much smaller), but one advantage of starting a repertoire database is that it encourages you to sit down and start looking at your games. Once you've checked out the opening, keep on going through the game....spot tactical errors with Fritz, ponder the positional factors, analyze the endgame.

To summarize: the purpose of the GrandpatzerBase-style repertoire is not to book up on theory. Its purposes are:

- To keep track of what main lines you've decided to play as your repertoire

- To record the opening lines you've experienced in the past, and your thoughts and analysis on them.

- To focus your opening study on the lines you encounter in your own games

- To allow you to search databases for games that pertain to your repertoire

- To encourage you to analyze your own games routinely and thoroughly

There's a time investment to get your repertoire database set up and to figure out how to use the software, but once it's up and running it's easy to maintain if you're diligent about analyzing your games.